LINES

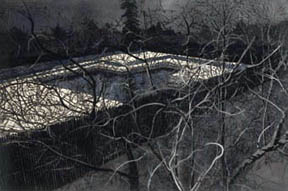

I fell in love with intaglio before I ever picked up an etcherís needle. From the first moment a fellow student showed me a freshly pulled print I knew this was something I had to do.Its surface was unbelievably rich, the explanation of how it was made was pure alchemy. How could I resist this invitation? Despite having practiced many printmaking techniques by the time I left graduate school in 1979, it was clear that my passion lay in line etching. My early work was largely experimental, turning out many one of a kind hand colored prints. The unique quality of etched lines has always been more important than the possibility of producing multiples. Even when the landscape became my most common theme, my interest lied less in rendering than it did in storytelling. Raising questions without providing answers became an essential element of my work. I eventually came to realize that what really interested me was the idea of landscape as metaphor to represent inner states of mind, At this same time I unexpectedly lost access to my printshop, and then refocused my artistic efforts on photography.

I did not pick up the needle again until 1992 when I began a new enterprise of supplying New England galleries with etchings of local scenery. Within a few years I walked over a thousand miles of coastline, collecting imagery and making contact with galleries stretching from Mystic, Connecticut to Bar Harbor, Maine. If the constraints of working within a business model left little time for experimentation, years of continual focus allowed me to hone my skill of observation and improve my drawing. The heavily etched lines that once defined my early work evolved into softer and more subtle tones. The one thing I never lost sight of over all these years was my desire to capture a true sense of place.

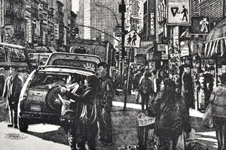

What made my New England series possible was attaining a studio at the SOHO Etching Workshop. I was still working there when I found a New York venue for my etchings in 1997. After that point, the focus of my work shifted back toward the City. I spent seventeen years there, turning my photographs of the city into etchings. This ended when the building was sold and I was evicted. This crisis finally forced me to confront my living as a transient and admit New York was my home, Soon after in 2012, I renovated my house to include a small printshop.

Although my home studio allowed me to continue working through the years of the Covid pandemic, the closing of shows and galleries hit my career hard. There no longer seemed be a place in the new world that was emerging for all that I worked for. While I found this depressing, it also had a liberating effect. Divorced from the art world, I recommitted myself to producing quality work based solely on my compulsion to make it. While my approach to the landscape as metaphor never completely vanished, I am now addressing this concept with a renewed rigor and am even more confident in its validity. One continuous line, drawn before recorded time stretches from the deepest recesses of the earth to my etching plate.

The links below lead to two separate portfolios, one for my New York prints and the other for a selection of New England prints. Each link contains multiple pages with work displayed in chronological order. All prints are made solely through line etching unless otherwise noted.

|

New York |

|

New England |

HOW MY ETCHINGS ARE MADE

At its core, etching is a transformative process powered by a chemical reaction. Acid is used to remove specific areas of a metal substrate through the application and manipulation of an acid resist. Metal smiths began using this process in the Middle-ages to decorate armor, often recording their designs by rubbing charcoal into etched lines before transferring them to damp pieces of cloth. Innovation, however rarely springs forth in isolation and etched prints do not appear until the sixteenth century after suitable paper and ink became widely available. It took another century of refinements before etching was perfected and taken up by artists in number. The technique has changed little since.

A number of different base metals can be used as the substrate for etching. Each has its own characteristics in how it can be worked and how it reacts to acid, which in turn determines the look of the line produced. Copper plates have always been the most widely used, though I use zinc. To control where the acid bites the metal, the plate is first coated with an acid resistant varnish called a ground. While grounds have no set ingredients, they commonly use bees wax for pliability, rosin for hardness, and asphaltum for durability. The quality of the ground used affects the quality of the drawing. If the ground is dried into a ball, it can be melted onto the substrate and then evened out with a leather brayer. Most modern grounds, like the ones I use come suspended in solvent and are applied with a brush.

Once dry, the plate can be drawn upon with a metal stylus. Both etching and engraving are defined as intaglio techniques, meaning to Incise. In engraving, a specialized tool is used to gouge lines out of the plate’s surface. This is very different from drawing and requires a skill that is not easy to master. While engraving came to dominate reproductive work, many artists began looking at etching as a way to free their hands from such calculated labor. Since acid is used to incise etched lines, only enough pressure to expose the metal lying under the ground need be applied. This allows artists to draw their lines in a more familiar and comfortable manner. Etching needles come in a variety styles, but their one common feature is that they have sharp metal points. While I hold my stylus as I would a pencil, this medium creates particular restrictions on how I can draw. I cannot impart tone with pressure, all my lines are identical. I only open lines for the acid to bite. The weight of a line is determined by the length of time it spends in the acid. The longer the exposure, the more metal is dissolved. The deeper the line, the more ink it will hold, and the darker it prints. I must also avoid exposing broad areas of metal for these will not properly hold ink. To create tonal fields, parallel lines are laid down and then more lines are crosshatched on top for optical blending.

When my drawing is finished, the zinc plate is placed in a bath of diluted nitric acid, which only dissolves the metal where it is exposed. To vary the darkness of lines on a single plate, a stop out varnish is used to seal off lines at various times within the etching process. The typical method is to complete the drawing and then remove the plate from the acid bath once the lightest tonality is etched. All areas to retain this value are then covered with varnish and the plate is etched again until the next tonality is reached. I now use an alternative method in which each tonality is drawn separately. Darks a put in first, etched, and followed by the middle tones, which are then etched, and so on until the lightest values are reached. Most of my plates are placed in acid at least fifteen times using this method. No stop out varnish is required but all tonal separations must be calculated before I begin to draw. The advantage of working this way is that lines of different weights can be more easily dispersed, creating greater tonal range and subtle transitions. The obvious disadvantage is that there is much more room for error. Etching is not a forgiving medium; not all mistakes can be corrected.

When all desired lines are etched into the plate, the ground is washed off and it is ready for printing. A pasty ink, a bit thicker than oil paint, is then spread over the entire surface and rubbed into the lines. When all recesses are filled, the excess ink is carefully removed in stages, aggressive wiping to start leading to more gentile whisking. The idea is to clean ink from the plate’s smooth surface so it will print white while pulling as little ink as possible out from lines that are meant to print dark. I do my wiping with tarletan, a product similar to cheesecloth, only starched so ink will only be scoop up in the space between its fibers and not overly absorbed into them. It is nearly impossible to wipe all the ink from a plate’s surface. That left behind on non-etched areas is referred to as plate-tone. Its presence is usually preferable since it helps to soften the image, making it more palatable to the eye. Since the inking process is performed entirely by hand, each print will inevitably contain slight variations even when efforts at consistency are made.

Printing utilizes an etching press, a variation of the rolling press originally designed to produce sheet metal like my substrate. It consists of a thick metal bed sandwiched between two heavy metal rollers. The top roller is suspended on a spring mechanism so the pressure it applies can be adjusted. A crank box or wheel turns the roller. After the plate is placed on the press bed, a sheet of paper is placed over it. Most printing papers must be soaked beforehand so they can stretch under the great pressure these presses provide. The paper is then topped with felt and woolen blankets to both protect the paper and force it into the etched lines. As this combination passes under the roller, the plate releases the ink and it is transferred onto the paperís fibers. The plate must then be re-inked and re-wiped for every additional print desired. Lines printed through intaglio are unlike those produced by any other printing medium. They create a topography of rolling hills and valleys, whose relief catches light in ever changing ways.

When the pass under the roller is complete and the paper is pulled back from the plate, it is a moment of magic. This is the first time I see my image in printed form. Up until this point, all the days and weeks of my labor have gone to creating a printing matrix that bears little resemblance to the print. The drawing on the plate is not only in reverse, the silvery lines exposed by the needle will print black while the remaining dark ground will appear white. The entire etching process is a very abstract way of working that few are comfortable with. It has been said that etching can be taught in a single morning but the practice takes a lifetime to perfect. For me, etching is also a concept, one that embraces transformation. While every medium might be considered transformative, etching is especially so because its production involves more than labor. In the making of lines, energy is both unleashed and harnessed through the use of acid. The nature of this energy goes beyond chemistry, It turns ordinary materials into art. It is hard to believe it is mere coincidence that etching arose at a time when Alchemy flourished.

Copyright 2024 Alan Petrulis All Rights Reserved