Mary Oliver

What other artists do I look at? Who do I read? It seems that if you can‚Äôt delineate a pathway to greatness, you can‚Äôt be considered great yourself. Is this a remnant of bloodlines that once determined everyone‚Äôs place in this world? Perhaps things have not changed that much. I always have problems finding an answer. While I realize that everything I draw, everything I write is based on the work of others who came before me, it is hard to connect the dots. When I work these days, I try not to think of what others have done. I pay little head to what is happening within the walls of galleries and museums. As for my writing, I’m as divorced from the literary scene as one can be. There are however moments when there is a flash and I realize I’ve crossed paths with a kindred spirit. While people often conflate art with self-expression, I don’t understand the relationship. I think this yearning, this compulsion to put pen to paper for a drawing or a poem has more to do with the desire to connect. We may all seek love and acclaim by trying to show how unique we are when we really want to know that there are others out there like ourselves, others who see things and understand things the same way. To truly be unique is to find oneself alone.

The poet, Mary Oliver was not a direct influence on my writing, I only began reading her a few years ago at the recommendation of a friend. What I found was someone who found the same solace and awe in the small hidden ponds at the tip of Cape Cod that I did. Her words to describe them were far more elegant than mine but differed little in spirit. Although we never met, she became part of my life by touching me through her words. This intimacy let me know that my own words had value. A soft snowfall falls as I write this. It is as indifferent to her recent death as it will eventually be to my own. It remains up to the living to find beauty and meaning in this world, a job made easier by those who help fill our hearts with poetry. I put down these words today because I feel compelled to say thank you Mary Oliver.

The Collective Eye

A recent attempt at retouching my own photographs beyond my normal limits has raised anew an old question; how much manipulation if any is permissible in a photograph? Even though this inquiry has been debated for years, the same old points are constantly rehashed and float around in circles with no consensus in sight. It seems to me that the basic foundation of this issue comes down to whether or not we believe that photography captures a truth that must be preserved. This of course is an illusion. Only reality is reality. All our attempts to capture it through art, words, or photo-mechanical means create nothing more than a distortion. We argue over which medium possesses the greater fidelity, but this is a fool’s errand. Even our own perceptions of reality are biased distortions dependent more on our evolutionary construction than what is really out there. We are not only limited by the senses we possess, we now know through scientific study that our own sight is based more on memory and mental projection than on optics. If this is correct, can we ever agree upon what we see? Does visual truth even exist?

Although the debate over honesty in photography has mostly been relegated to the field of photojournalism, there have been plenty of instances where photographers working as artists have been taken to task over the same sort of manipulation. We all seem to have a mad obsession to define what separates things and each other. The impulse of course is primal to our being; it is after all how we come to comprehend the world around us or at least get enough of a grip to function in it. Unfortunately too many of us carry this tendency to the point of becoming purists, where shades of grey are seen as anathema. Genetic based tendencies to define often run afoul with our generous ability to extrapolate beyond our senses, which can cause us to distort reality dramatically. To me the desire to clearly define the world speaks more to a personal compulsion than a high ideal. When truth is held up as the principal model for photography I don’t know how that is accomplished. I don’t even know what that means. This debate has been exasperated further by the algorithms through which digital photos are processed. Many cameras today have interpretive settings for landscapes, portraits, action shots, and flowers as if there is some sort of inherent difference between them. I’ve never seen a programmable mode for truth or reality.

The security cameras that now proliferate in our streets have an unbiased eye. There is no question of them editing anything out for the sake of expression or aesthetic appeal; but these are not the images we give awards to. We cry for neutrality in vision yet reward those with the most unique results. We can’t seem to ever admit that we don’t really want what we say we want. Through centuries of traditions we have created an idealistic view of the world that is based on nothing more than abstract constructs in our head. This is why rhetoric based on high ideals can rarely satisfy our true desires. The desire to reproduce reality in high fidelity has been an age old quest, but as soon as we drew close, we quickly began drifting away from out goal. Natural color printing is commonly replaced these days by heightened hues worthy of 19th century chromolithography. A quest fulfilled becomes the norm and thus something to challenge once more.

I consider myself an artist, not a photojournalist; so much of this argument over truth has no immediate relevance to how I create my own work. This is not to say that the art world is not immune from such thinking for it is filled with purists. There seems to be an endless supply to the dos and don’ts I‚Äôve been subject to ever since entering grade school. I‚Äôve learned to ignore them all as best I can for in the end they seem more about confirming status and order than anything to do with art. These however are still powerful forces; and while I can hold my own in mediums I am comfortable with like etching, some uncertainty still lingers when it comes to photography. Even though I view all media as nothing more than a tool to convey a message, digital media has opened up a whole new set of undefined parameters that I find myself uncomfortable with. I may have no need to define what I do, but I still live in a world that expects me to function within definitions that it can no longer properly articulate. We can have different ideas about what we see, but when we don‚Äôt share the same language when we try to compare personal vision, problems arise.

For many years I rejected using a digital camera simply because I did not like the results they provided. Regimented pixels were no substitute for the subtleties of the random molecules found in film grain. This may still be true, but the ability to manipulate digital photos through software to the extent I can now do has made me a convert. Perhaps this is due to my initial interest in photography as an information gathering tool. Pictures taken were not an end in themselves; they were transformed into other works in ink and paint. While I now view my photographs as finished pieces, I find myself confronted with a grey area as I push this process further. I’ve learned to accept the results as a photograph when the image retains most of its photographic properties; and when it approaches something that looks more hand drawn, I am happy to call it something else. The borderline between the two however is still in question. This resembles arguments over what constitutes good photojournalism, and the solution may lie in a realm where most of us do not want to go. An ill-defined boundary may not be the issue at all but rather my search for a border that may not even exist. If photography is just a means to an end, should I be asking this question at all?

There have been efforts to define the parameters of photography since its birth but it has not been easy to keep it in its place. The early 20th century in particular produced a number of photographers that exceeded traditional limitations. In reaction, curators, writers, and critics left us with mountain of new arguments and perspectives on how photography should now be looked at, thus unintentionally creating a new set of limitations in their attempts to break them. While much of this discourse is still cited today, the relevance of so called experts has been waning for some time. New artists are redefining photography without any regard to the masters of the craft since we don’t see with a collective eye.

In this new digital world is there even a role for photographers beyond their own celebrity? Despite the accolades bestowed upon them, real achievements barely seem to be recognized today. Photographers continue to fight among themselves for a place in the sun, still using antiquated arguments to support their cause. Some things don’t change or change very little because once a support system is established it is very hard to overcome. Most arguments come down to definition; not about aesthetics but how every painter, performer, and writer finds a place in our society. Most of what has been bothering me over defining digital photography may have nothing to do with art at all. Ultimately these are only arguments over ego, social status, and marketing. Artists constantly complain that digital manipulations of photos are just cheap shortcuts to real hand drawn work even if the results are identical. The world is inundated by photographic imagery not taken by photographers, at least not by those who have studied a craft. It’s not art that is being protected by old arguments but the investment in the exclusivity of being an artist or photographer.

As for my own work; I see that I’ve been letting too many voices outside of my own inclinations cause confusion. I’ve imprisoned myself by thinking in terms of photography and purely hand made art because there simply isn’t a name for work that is neither. There is not yet a new class of established practitioners to protect. Old definitions are disappearing but not fast enough to completely recognize the new pictorial landscape arising before all of us. Artists will always be needed as long as some in society remain interested in expanding vision, but if I am to do this I need to trust my own intuition. The photographer Robert Frank once said, “Doing something is better than doing nothing.” I think that’s all the philosophy I need.

This is Not a Magritte

As I rambled across the dunes of Cape Cod a distant hill framed by two stunted pines caught my attention begging to be photographed. It was only much later while looking through some older work that I realized I had captured the exact same composition nine years earlier without the slightest recollection of having done so. The only difference between the two shots was that the newer photograph was taken in the harsh light of summer and the other on a grey drizzly autumn day. My trek had taken me over highly broken terrain devoid of trails; the odds of arriving at this exact location twice were high, the odds of framing the same composition twice seemed phenomenal. Of course what sometimes passes for coincidence may be in fact nothing more than the results of limited perception. Perhaps a seemingly random walk is guided by subtle nuances in the terrain that one is barely aware of. All the scenes we take care to capture in our photographs must be singled out by some internal criteria, conscious or not from the incessant visual stimulus that surrounds us through our days. The question is, where does that criteria that silently guides the photographers eye come from? This too is the question raised by the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Walker Evans exhibition that compliments the work of this great photographer with a large sampling of postcards from his vast collection.

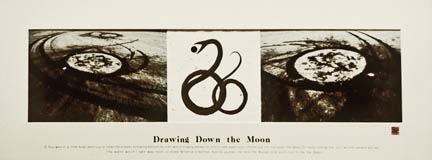

The cave paintings of our most ancient ancestors are usually spoken of today in artistic terms, but we can only speculate to what these markings meant to those who created them. Some understanding may be gleaned if we delve into our own humanness while discarding the fads and rhetoric of the gallery and museum scene. With no conventions to follow, these pictures must have been drawn from an inner voice; one that might not have been conscious as much as something within attempting to create consciousness. Set into the deepest recesses of the earth, their creation mimics attempts to delve into the darkest regions of the mind as if we and the planet are one in the same. If this scenario seems at all plausible, it is only because of the disclosures made by more modern artists who have revealed their own attempts to take this inward journey.

These ancient pictures drawn in caves were not the commodities that now define the art world but were made as pure magic. As pictures evolved into letters and numerals they continued to retain much of this magic. Many once understood the power to be found in words that went far beyond mere communication. Words held even greater potency once they were written down. When different belief systems began competing for supremacy, most of these esoteric associations gradually disappeared along with respect for magic. Although certain words still engender enough power to be banned or at least disparaged while others found in holy texts continue to play a crucial role in religious rituals and rites, for the most part they have lost their authority to command us. This is very evident in our society that has grown more literate, but in which too many still fail to acquire basic reading skills. While blame can be dispensed in a number of directions, this problem exposes a more serious decline in respect for the power inherent in words. Children often fail to learn to read because they do not comprehend the real loss that accompanies this failure.

Although some artists continue to combine words and pictures as coconspirators in the creation of magic, the two have generally become segregated because of how we define them. When words are paired with images today, it is often to explain away what we no longer have the power to read on our own. When there is no inherent understanding of an image, we search for meaning to fill the void as if this were an acceptable substitute. By pursuing meaning we just drive ourselves deeper into our own abstract thoughts at the expense of experiencing the real world. Through this process words have grown paramount to the point of creating their own reality. As words have become confused with the literal, our perception of the world is shaped and limited through the structure of the language we speak.

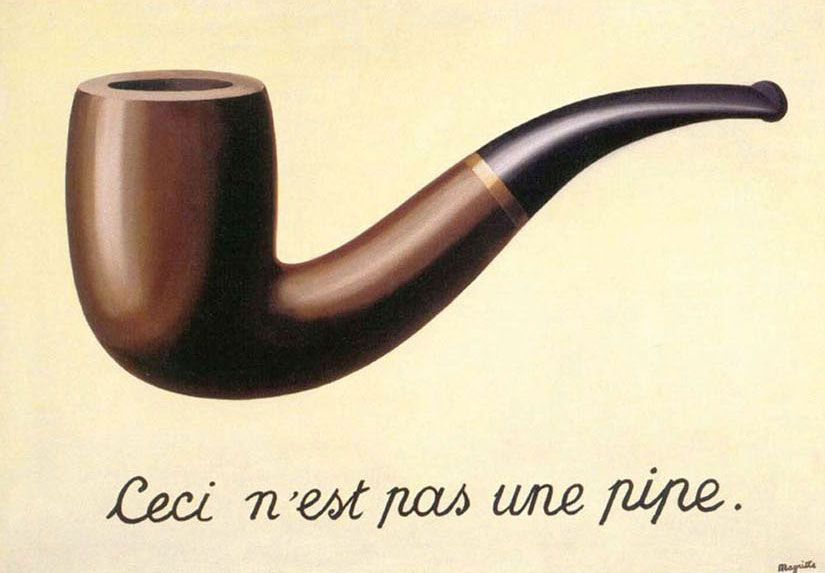

When I stumbled upon the old postcard pictured above with the caption, IT’S A PIPE, I thought it nothing more than a strange curiosity until I read the hand written message on its back, Do you think it is a pipe? It suddenly conjured up an association with René Magritte’s painting, Ceci n’est pas une pipe (This is not a pipe) pictured below. The painting dates from 1929, and the postcard was produced about twenty years earlier; so does this make it a precursor to this famous Surrealist work? This card, published by Theodor Eismann, was most likely part of a larger set involving some common form of wordplay. At this time word games and rebus were not only popular but considered a high form of humor. Though these games are very prevalent on antique postcards, their purpose was not to impart philosophical insight; publishers were only vying for attention to make a sale. Despite the publisher’s intentions, this card with its message presents the same quandary as the Magritte painting; asking us to reexamine the way we look at pictures in relation to the written word. While Magritte may have never seen this card, It is difficult to imagine that he was unaware of this postcard genre considering how prevalent it was in popular culture.

Even if Magritte was familiar with wordplay postcards, he refocused these issues away from playful novelties to the fine arts where they would truly become subversive. His work constantly undermines the ways we perceive the relationships between the world, our visual representations of it and names we give to it. By confusing abstract thoughts with the literal when placed into language, societies fail to separate the symbolic way we present visual imagery from reality. Magritte does not present us with a pipe but paint on canvas, which creates a visual illusion that acts as a symbol for a pipe. The purpose of his art is not fidelity in rendering; Magritte actually offers us an invitation to attack his own stylistic conventions, and by doing so change the way we see.

Over time we can see how philosophers described the world in very different terms from the more ephemeral visions of Descartes to the more substantive reality of Kant. These men were not born with eyes so different from each other; it is the way they interpreted what they saw through the filter of their existing language that shaped and created their divergent thoughts. Modern behavioral scientists have now proposed that the reality we say we perceive with our eyes is only partially based on visual stimulus. An exact mirror of the world may be reflected onto the back of our eyes, but as this information is passed on for interpretation, it first mixes with preconceived notions held in our memory before forming a picture of reality in our mind. It is this trait that probably helps us recognize reality in pictures, but as a consequence we sometimes mistake symbols for reality. There may only be one reality out there, but it is different for each of us. The more we are separated by language, the greater our differences in perception. This is not only true between cultures, but within the same culture when separated by time.

The realist traditions of the West often persuade us to believe that artists can render the world in an objective manner as long as we are also blinded by the same language of vision. It is other people that distort reality; we only see the truth. While we may bring ourselves to believe that the society we live in is nothing but an illusionary human construct, the idea that our perceptions of the world are based more on pre-existing bias than empirical stimulus is much harder to accept. Artists like Magritte may try to remind us of how easy it is to become a prisoner of our own words, but these chains are difficult to break. Even if we can transcend these constraints through myth and metaphor to see the true essence of things, there is a greater tendency to forsake them for a language that places the world in more exacting terms. This may be the result of nothing more than an evolutionary tendency to find comfort in the concrete, for there is safety to be found in a world that does not change.

Magritte’s world was not shaped by determinism or chance, nor did he believe his actions had much if any effect on it. His art was not meant to change things but only open a window clouded by language through which we might better see the world. For him this required a freedom in waking life that is similar to that we have when dreaming. If vision requires more than light reaching our eyes, then understanding must come from a source beyond the distortions of logic and the accumulation of what we call facts. While myth, metaphor, and poetry can supply us depth and help us grasp what we see, we must also be careful not to forget that these too are only relative truths so we do not create another distorting lens to see through. Artists must remain true magicians, not to create illusions but to break them.

For those who dislike change, postcards may supply a pleasant nostalgic look back into a world frozen in time. Despite this stereotype, it is a mistake to believe that postcards do not present us with important insights into their time just because they are such a familiar feature of popular culture. It would be like a scientist dismissing Hydrogen as being crucial to the understanding of chemistry because it is such a common element. Postcards were once so pervasive within society that they form a microcosm of their world. The question of what to depicted and how it was to be represented is often more important than historical documentation. Through a bit of reverse engineering we can get a glimpse into the commonality of language that molded this past reality. To understand postcards, we must view them in the context of their times, but through the careful examination of postcards we might just discover the essence of these times.

A Question of Boundaries

I wasn’t looking forward to visiting the Dia Art Foundation in Beacon as the institution houses most of my least favorite artists of the 20th century. As it turned out this former industrial facility built by Nabisco and now converted into a museum was such a perfect environment to view this work that it enabled me to see it with a new perspective. I was very irked by the no photography policy for the balanced between the interior and the art on display created an intricate landscape that I was dying to capture. Its long wide galleries bathed in natural light from almost endless rows of skylights did not just hold the work but interacted with it; each individual space rendered a work of art in itself. While a new appreciation grew for pieces previously disdained the entire experience raised important questions regarding boundaries. Art‚Äôs ability to expand beyond the confines of a frame is nothing new but how dependent it should be on the environment it is placed in is still a matter of conjecture. This is not a question of whether a work is displayed well but rather its ability to function on its own merits. Here groups of paintings completely illuminated rooms with their spirit, and yet if seen individually I could have just walked past them with barely a moments glance. As taken as I was, what does this say about the art itself? Does it fail if it is completely dependent on its environment to be appreciated, or must we just redefine our own prejudices to where the boundaries of art might lay?

This question was on my mind as I approached the one piece I actually came up here to see, You see I am here after all created by Zoe Leonard in 2008. The title is taken from an actual line written on one of the more than four thousand postcards of Niagara Falls that make up this instillation. The cards are amassed into grid like blocks and shapes that single out images taken from specific viewpoints. This allows each block to register as a whole despite the fact that many of the individual cards were printed very differently. Even though the Dia galleries enhanced nearly all the work on display I was very disappointed to find that it actually detracted from this one. The great expanse of this piece was somewhat lost in the dark narrow space that it was mounted in. Well over a hundred feet in length it unfolds as a scroll rendering it contemplative at the expense of its more formal aspects. Though the dim lighting may have been due to efforts to help preserve these cards, most over a hundred years of age, this should have been taken into consideration when first conceived. It would have surely projected more power, like the monumentality of the waterfall itself if not forced to be viewed in such a linear fashion. The postcards have enough pull to draw the viewer in close even if first seen from across a wide expanse. Its obvious dualities were severely compromised by placing it in a space reminiscent of a hallway whose doors interrupt its flow. The major problem with the environment selected for viewing was not its effect on aesthetic appreciation as much at it skewed the meaning of the piece by giving artificial prominence to one aspect of it over another.

I am often frustrated with the art world’s inability to see beyond the boundaries it sets up for itself, even when dealing with boundless art. Leonard should be applauded for not only challenging the public’s perceptions but the stale notions of so many cultural institutions. This said it is unfortunate that this instillation's ability to project multiple levels of meaning does not go as far as it may have been intended. The sheer number of old postcards the artist was able to find is testament to the pull Niagara Falls has had as one of this nation’s oldest tourist attractions; already a popular destination in the 1820’s as part of the Fashionable Tour up the Hudson River. In competing with the Grand Tour of Europe the Falls became a symbol of America and one of the first images to be placed on our postcards. Over time Niagara became more of a commodity than a place; a concept heavily reinforced by the mass production of mementos. The postcards chosen for this piece however do not depict the tourist side as much as the Falls as a natural wonder. While the naturalness of the images forms a nice though somewhat uneasy balance with the abstract formality of the instillation, it mimics the contradictions between sublime revelation and the honky tonk honeymoon capital tourist trap that Niagara became. In more recent years tourists have begun flocking to other types of amusements that offer even more spectacle and adrenaline rush, which has allowed the Falls to disappear from its high perch in public consciousness. If Leonard‚Äôs piece is asking its audience to contemplate these older connections there are notions that need to be already present in the viewers mind that for most no longer exist. While art should raise questions it is not prepared to answer, the limited and discordant vocabulary of today’s audience render the tenuous dualities of this piece far less effective than its ambitions. Those let down by their first impression of Niagara were often told that the Fall’s sublime aspects could only be appreciated over time. Perhaps this needs to be considered here as well for despite the work’s shortcomings it still provides us with much to ponder.

Incongruities

In his book Mountain Light, photographer Galen Rowell relates a story of his encounter with a yellow cab out on the Nevada desert. The contrast between this urban conveyance and the open red landscape that surround it are strangely pronounced, yet he holds back temptation to shoot it. For Rowell this scene consists of elements so out of place that he is unable to make a personal connection with it. While I understand the value in trying to capture a true sense of place, I have always been troubled by his reasoning. It seems to me that no matter how unusual something may appear to be it is still as much a real part of the place it is found in as anything else. A scene is what it is, all problems that may arise from it originate from within. This does not mean that everything is equal for there is value in composition and narrative that cannot be ignored. One must be careful however not to confuse the artistic editing a scene of what does not work from sanitizing compositions of elements that do not fit in with preconceptions of how something should appear. Too often we have such strong emotional responses to what we see because we so tightly frame the world with our own personal definitions while refusing to open our eyes.

When I found this old real photo postcard depicting a scene somewhere on the border between New York and Vermont I was immediately taken by the unexpected combination of subjects it contained and could not help but remember Rowell’s story. This snow filled valley is the most peaceful of scenes with a paleness that gives the impression of gently falling flakes. Yet in this quiet we are confronted by a police officer mounted on a blanket draped horse, both of whom stare at us intently. Is this a planned pose carefully set up by the photographer or a chance meeting out on the road? Would not a small town sheriff be more appropriate to this rural scene if out on patrol than a uniformed cop? No answers are forthcoming to a swarm of questions that arise and the tension heightens.

I doubt very much that this unknown photographer had any intention of creating as surreal a looking image as it appears today. I am equally confident that the whole scene must have seemed very matter of fact and ordinary at the time when he snapped the shutter of his camera. If drawn this scene would appear totally contrived, but as a photo it is only awkward, nothing here seems coerced. The intensity of this image is not derived from its subject but through our disassociation with the circumstances from which it was shot, forcing us to reflect back in on ourselves. This image may not capture the essence of this place but it certainly is of this place whether we can understand it or not. Sometimes questions are the answers.

The Lyric Documentation of Walker Evans

As I rambled across the dunes of Cape Cod a distant hill framed by two stunted pines caught my attention begging to be photographed. It was only much later while looking through some older work that I realized I had captured the exact same composition nine years earlier without the slightest recollection of having done so. The only difference between the two shots was that the newer photograph was taken in the harsh light of summer and the other on a grey drizzly autumn day. My trek had taken me over highly broken terrain devoid of trails; the odds of arriving at this exact location twice were high, the odds of framing the same composition twice seemed phenomenal. Of course what sometimes passes for coincidence may be in fact nothing more than the results of limited perception. Perhaps a seemingly random walk is guided by subtle nuances in the terrain that one is barely aware of. All the scenes we take care to capture in our photographs must be singled out by some internal criteria, conscious or not from the incessant visual stimulus that surrounds us through our days. The question is, where does that criteria that silently guides the photographers eye come from? This too is the question raised by the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Walker Evans exhibition that compliments the work of this great photographer with a large sampling of postcards from his vast collection.

I had known for some time that Evans collected cards but had always assumed they were real photo postcards that directly related to his own professional interest in photography. I was quite shocked when I had a chance to actually see them. His cards were not only of the printed variety, they were quite ordinary. Ordinary of course may seem like a simple word to define but it can be froth with subtleties of meaning. Evans often referred to the types of cards he collected as examples of folk art to denote their lack of sophistication. In his mind they basically served as raw documentation, designed without all the pretentious layers of concerns heaped upon the deciphering of fine art. But while millions of postcards were produced without much, if any artistic value there were also countless numbers that went beyond mere documentation. Evans had compared this trait to the scientific drawings of Leonardo, created for practicality but presented with all the mastery and vision found in his most accomplished works of art. This Evans described as “lyric documentation,” a term he coined at Yale University in 1964 during a lecture he gave on postcards, and subsequently applied to his own work.

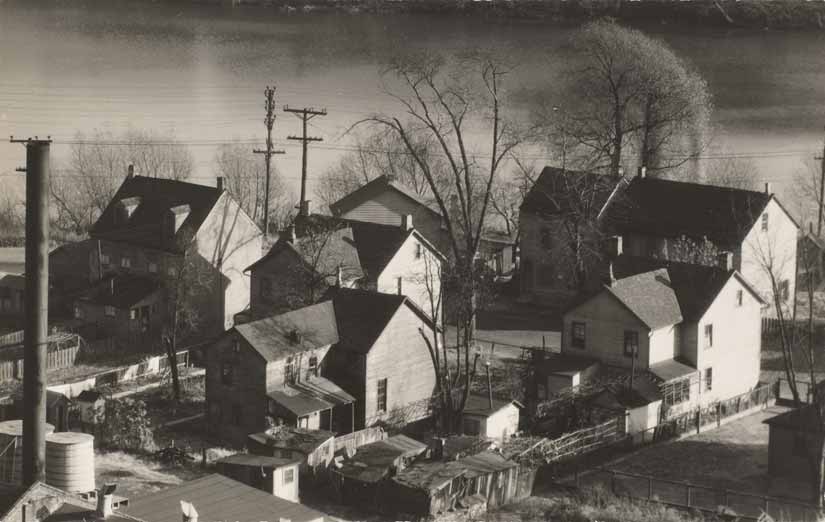

While nearly all postcards were manufactured as a sellable commodity the rationality behind choosing individual subjects varied a great deal. Important landmarks and tourist destinations were obvious choices but general views of our city streets and the byways of small towns were also captured in numbers beyond anything found on postcards today. Many other subjects on these old cards were depicted nowhere else. We can tell that it was these street scenes that interested Evans the most for they make up the bulk of his collection. Some of these scenes were created from photos taken by local residents, particularly those who could sell them in their own stores, while others were the handiwork of itinerant photographers working for publishing companies. When the least amount of care was given to the framing of the composition the resulting photos tended to lack many of the superimposed notions of what a ideal landscape should look like capturing instead a real sense of place. Though many images were retouched before printing, everyday detail was largely left in of that place and time. With the distance of time it is now easier to read those images with a fresh perspective that can allow the lyrical elements to outshine the outdated meanings placed on them in their own day. Evans ability to see this lyricism in the present of everyday life guided his own work.

In many ways it is surprising that Evans followed such a simple path. After his return in 1927 from a two year stay in Paris he settled in New York City and began taking his first photographs a year later. His strong anti materialistic views and rebellious nature made the socially unacceptable bohemian lifestyle attractive to him. The career of artist was not something decent people aspired to and there was even less respect at that time for photographers. But the Great Depression that soon cast its shadow over America made it easier for Evans to evade holding down a regular job leaving him more time to pursue his photographic interests. “Always against the grain” as he put it, he approached his taking of photographs in a manner he considered anti-art. His associations with the New York art crowd imparted little influence on him as he pursued what was least acceptable to them. Evans felt that to be part of the art world establishment was to be tamed into producing works of stale conventionality. But his distain for forcing images to serve a greater purpose outside of the vernacular also kept him away from a more intellectual outlook as adopted by others in his circle. Evans continuous belief that he was on the right track kept him from straying from his own ideals.

Evans always claimed his work was born of intuition not intellect. He also assumed this was generally true of most other photographers as well, whether they admitted to it or not. He even went out of his way to label certain photographers such as Steiglitz, “decadent” for trying too hard to force mood and meaning into a photograph. Evans however remained blind to his own prejudices by seeing them as something natural. In many ways the simplistic attitude he presented did him a disservice for Evans was truly a modern photographer of the 20th century. His use of high contrast and stark cropping of subjects created abstractions that were certainly deliberate in a way that would have been unheard of just forty years earlier. When one examines Evans’ most famous works, those scenes from Appalachia taken as part of the Farm Securities Administration project during the Great Depression, we can easily see that cold hard matter of fact style of his. It is also easy to see that these photos hold a great depth beyond definition despite their documentary approach. Evens was aware that something lyrical shown through these ordinary images just like they did on the simple postcards he collected. When Evans states that the lyricism in his work comes from intuition rather than intellect I believe that he believes that’s true. But to isolate himself to a single narrow focus in the world of ideas that he sat in is very much a conscious philosophy in itself whether he recognized it as such or not. His singular intent seems to come more from a purposeful lack of introspection than any attempt at manipulation. Perhaps this has to do with his modest Midwest roots, but I cannot help but wonder if his failed attempt at becoming a writer in his younger years left lingering fears that prevented him from confronting his latter career in photography to any significant depth.

Evens let it be known that he had his doubts that the photographers that produced the images for postcards had any real intentions of capturing the lyrical but often did so despite themselves. This idea most likely arose from Evens’ struggle to understand his own work. Despite his early infatuation with postcard imagery it took him awhile to clearly understand what it was he was really interested in. This can be seen when comparing his early work to the same images reprinted as real photo postcards in 1936. As to be expected he began by following a more traditional and thus acceptable approach to composing a landscape despite his cries against unconventionality, while his later postcards are severely cropped down from the much larger negative to strengthen the image’s internal poetry revealing what truly attracted him to the scene in the first place. It is often not a matter of what one sees; it’s a matter of courage to say that there are other ways to perceive the world from that which we are accustomed to. Jeff Rosenheim, the curator of the exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum states, “I believe he had the ability to see the present as if it were the past and to create a body of work that stands the test if time . . .” I believe it is just the opposite. Evans’ gift was to be able to live in the moment and reject seeing the past, eliminating overtones of sentiment and nostalgia from his work. His photographs are timeless for this disconnect weakens cultural ties to reach what is human within all of us. This may be a fine point to argue since we both agree on the final results but it makes a world of difference when living it as compared to just observing it.

In reading Evans’ remarks concerning postcards and in comparing the images found on his cards to his own photographs there can be no doubt that a connection exists between the two. This appears most evident in Evans’ photograph of Morgan City, Louisiana which shares its empty straight forward composition with the same wide street and distant river found on a postcard from his own collection. Some have said that the relationship between these two cards is just too great to be a coincidence, but is this really true? We need to come back to the question as to where does the criteria that we select imagery come from? To state that the postcards Evans collected since his childhood created an aesthetic that influenced his later photographs would be too simplistic. I believe what ever inner voice caused Evans to choose those specific cards that he added to his collection above all others was the same voice he later came to depend on when composing his professional photographs. The postcards did not so much guide his style in the direction that it took as much as it reinforced his innate intuitive vision that allowed him to follow a course beyond the ordinary with conviction. That none of his other photographs match any of his postcards to this degree makes it even more likely that the Morgan City pairing was not a deliberate creation. If it was his postcards that directly influenced his compositions as a photographer even if only in spirit, what was it that influenced his decisions to purchase those cards? They appear to be selected with the same discriminating eye from which he later created his photographs. We can continue to extend this argument even further by asking what influenced all the photographers that took the photos from which these postcards were made?

I first became familiar with antique postcards at small New England museum that had numerous cards on display depicting local scenes. I immediately fell in love with them and wished that there were some way to add these little works of art into my life. It was only a short time later after being introduced to postcard club shows that I began to purchase my own cards. With a limited budget I had to confine myself to picking out only those images I could incorporate into my artwork, but it did not take long to find myself constructing a small collection of pictures that I did not really need but could not live without. Even so I partially rationalized this endeavor by placing restrictions on location and subject matter as if by categorizing them in definable ways it would be okay to spend scarce funds on these nonessential items. It took many years before I gained the courage to start buying postcards based solely on their more indefinable artistic merits. As it turned out it was those images that shared the same sensibilities with my own work as an artist that appealed to me most regardless of subject matter. Evans, who began collecting postcards when he was only eight years old, had no such adult concerns to justify. But even while approaching this activity with childhood exuberance, he too was drawn to possessing images of certain character.

While most of us superimpose some sort of order on everything we look at to the point of blinding ourselves to the real world, some possess a deeper ability to see. But even if this trait is a natural one, it still needs to be nurtured for it not to be buried under the artificial environment in which we surround ourselves. A strong conviction is also required to push the boundaries of tradition to the point of actually expressing ones vision for anything different is always met with resistance. Evans did not consciously recognize that he had this vision as a child when he ran into a five & dime to emerge with a handful of postcards. But each of those 9,000 cards that found there way into his collection required an aesthetic choice to be made, and each of these decisions had the same function as if he snapped his own camera’s shutter to capture them. His ability to see is something he had to learn to recognize and pull out of himself before being able to become a successful photographer. His postcard collection helped him find that path and it gave him the courage to stay on it.

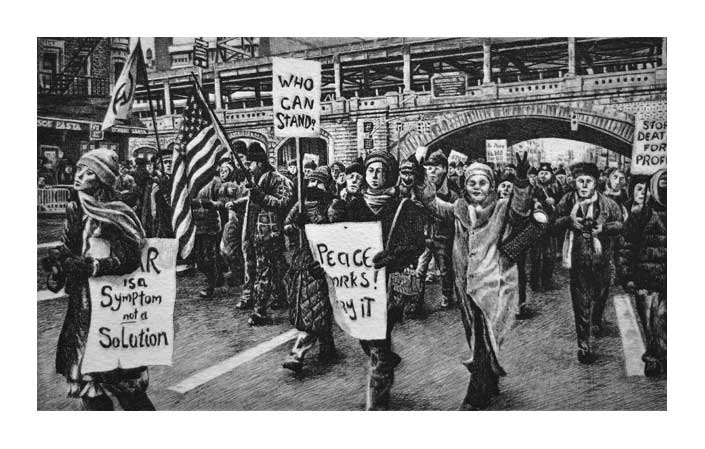

Statement for The Art of Democracy

A recent MTA ad campaign proudly proclaims that last year 1,944 New Yorkers “saw something and said something”. Since no bombs were found and no one convicted for terrorist acts it might as well have read that 1,944 innocent people were harassed by the police for no good reason. While this number has since come under scrutiny for possibly being pulled out of thin air, I can vow that at least one of these calls was real, the one directed against me.

A police presence on the street was once a comforting sign; now more than thieves it is the police that I keep my eyes wide open for when exercising my Constitutional rights. Being told I cannot take photographs from a public street has become a regular routine. This would be bad enough if it were a matter of law but I find myself being subject to the whims of the individual officers I run into. While this scenario has played itself out a number of times it took a more serious turn when a motorist spotted me with my camera crossing a bridge and dutifully placed a call to 911. After being whisked away in a patrol car I spent the rest of the afternoon at a station house being interrogated as to who I was and what I was doing. I kept thinking that once they found out I was an artist they would let me go but I just faced additional interviews by new agents. The Judge I finally appeared before was far less sympathetic than I had hoped. I was basically told that in these times I should know better, that taking pictures of bridges is no longer allowed. We now have a legal system consumed by fear rather than justice, where intimidation has replaced law.

I do not consider myself a political artist and these tribulations have not inspired me to become one. I feel that there are more effective venues than art to express my political outrage. But I have also discovered that there are times when one must make the effort to have ones voice heard even if no one seems to be listening, to take a stand if only to be counted for what one truly believes. Freedom and liberty are not compatible with nation unwilling to assume risk. The cowardly cannot tolerate art, only pretty pictures.

Statement for A Day at Coney Island

Descending upon the landscape with pencil and paper in hand had always proved problematic for me. Whenever I came across a view that was appealing I would wonder what was around the next corner or over a distant hill. Photography became the natural way for me to sketch, suiting my restless disposition. Not only have I found this liberating but it has helped to develop a look to my work that has a more contemporary feel; one that would seem out of place to any landscape artist of the early 19th Century despite using a similar technique. As comfortable as I have become using photography it still has many limitations and is no substitute for the eye. If I can create an etching that is solely based on one photo I consider myself lucky. As I wandered about Coney Island I thought this fortune had found me as a single shot of the carrousel inspired a long composition. But elements of the photo just didn’t work requiring me to gather more information. Instead of correcting the original composition, I ended up creating a very different one. But there were still parts that would not work together so back I went for more shots. This finally allowed me to create the etching “Carrousel and Wonder Wheel,” a scene that is meant to capture the spirit of place, not the sum of its photographic parts. Photography is just one more tool available to work with. In the end the artist makes the picture, not the camera.

Statement for Tide Lines: Contemporary Staten Island Waterfront Prints

As a record snowfall hit the City I listened to commuters complain about their difficulties in getting to work on time. It was a stark reminder of how so many people are so fully embedded in an artificial reality that when suddenly confronted with the real world, they can’t understand that maybe they shouldn’t be traveling in the snow. It is because people live this way that they don’t see where they live. As abandoned waterfront turns to parks and condos, most applaud the return of functionality not understanding what is lost in return. That which feeds the soul is rapidly being replaced by an epidemic of sameness and sterility. It was only after the fact that I noticed the images I chose fore this exhibition, whether oil soaked pilings, rotting tugboats, or sagging buildings waiting to be demolished, all shared the common thread of being “eyesores.” Beauty is not the absence of the ugly; in fact it often embraces it.

Musings on a panel discussion at the School for Visual Arts: How has the Digital Revolution altered the domains of printmaking and photography?

After an obviously manipulated digital image won first place in a photography contest, the sponsoring magazine was deluged in a record number of letters of complaint. The winning image, a computer generated montage happened to be very beautiful but for many it raised questions as to how photography should be defined. This was on my mind as I entered the SVA auditorium along with a number of other questions that I had been mulling on over the years. I arrived with some hope that answers might be found in the discourse that would follow. By the time it was over I had more questions than when I arrived.

The artists in the panel were all heavily involved with digital technology often moving back and forth between new and more traditional methods. Although I appreciated listening to their various approaches I was taken aback by the matter of fact attitude of some panelists as if the digital revolution was a fate accompli. Many in the audience were angry. There were those who dedicated their whole life to working with film only to now find that not only has attention redirected itself away from them, but that they are faced with mounting difficulties in carrying on their craft even if to a more select audience. As practical questions were raised they were met with vague answers such as new markets and sources for photo supplies may eventually emerge. But these people needed answers today. How does one pay for groceries when no one is supplying the materials necessary to create one’s work? How do you set prices for this week’s appointment when there is no consensus on what even constitutes a photograph?

My most vexing questions were not as specific but no less relevant to my own everyday work. Digital reproduction has already blurred the boundaries between traditional photography and printmaking as images manipulated with computer software and spit out of an inkjet printer are both currently being labeled as photographs and as prints depending on the whim of the artist producing them. If artists cannot agree on definitions how is the public to acquire any sense of understanding? When I had the chance to add in my two cents I inquired about the long standing paradigms that separated photography and art. Photography, though manipulated since its inception, has always been perceived of as a genuine slice of life. Art on the other hand can be characterized as a falsehood for it is always the product of an individuals biased vision. Even when we know that the dichotomy between truth and fiction is fraught with exceptions, there has been an unyielding general perception over many generations that this arrangement is such. Even to this day there are those who will not concede that photography is art, and if it is, most see it as a poor relation. In the face of such resistance that is over a century old, how can it suddenly be declared that the world has all but accepted digital media as the equal to prints and photography? While there was some realization that there was a crisis in definition, their general solution was “history will sort things out.” Well yeah, but that’s not an answer.

We are all entering a new age where visual truth and fiction are melding together, an age in which only a major paradigm shift can keep art defined. Can we expect such a shift? Looking back on history it seems unlikely, at least for the near future. What we may be asking of ourselves is beyond the possible. Our perceptions are not just based on personal beliefs or cultural outlooks. No matter what we say we believe in our perceptions are first base upon countless years of evolution. Is our culture shifting in a direction that requires us to be less human? What happens to art when these conflicts cannot be resolved? Magic cannot truly exist in a media where illusion has become nothing more than a common commercial skill.

Those who are purists seem to make up a significant proportion of all societies. They are the type to complain when a watercolorist first sketches in pencil or when a printmaker plays with plate tone to create a unique etching. They are among those now criticizing digital photography. I am not one of these for I do not believe in rules that inhibit the creative process. It is the final product that matters, what is says and its relatable properties. But the idea of embracing the new is often little more than a marketing ploy for there is very little that is truly new in art. Boundaries are essential for us to be able to comprehend, even if we are reacting against them. A good artist presses the limits of these boundaries but knows that work produced must still fit within a context that an audience can understand. Without understanding, if only in part, there can be no transformative experience, which is the essence of art. Without understanding the public resorts to seeking out clichés and the sentimental while artists engage in work that is nothing more than self indulgent. The birth of photography was truly new and revolutionary. Despite this it has been presented as much as possible within the same familiar framework as art, and when its own uniqueness does shines through many fail to comprehend.

Digital media is new territory for all of us that create or just look at art. It has become part of a long list of growing problems affecting many areas in our lives arising from a natural desire to hold onto beliefs that give us comfort that conflict with a technology developing faster than we can comprehend or even control. There can be no decree from above to settle these matters, nor should there be. What is needed is an honest dialog. Unfortunately while most of us have our heads in the sand, too much of the debate is not being directed by artists but by big business. Cameras and film are manufactured for snapshots not fine artwork, for the bottom line is profit. Specialty items have long been manufactured as a derivative of common products for the masses, but artists alone cannot support an entire industry required to manufacture film, papers, chemicals, and process them. Artists will continue to work regardless, but loosing the ability to practice skills accumulated over many years is not just a loss to the artist but to society as a whole. Will it be possible for anyone to a master their craft if new software to be learned is developed every year? We now stand at a crossroads whether we feel it is of our own making or thrust upon us. If we refuse to choose a path we will all fall into the abyss.

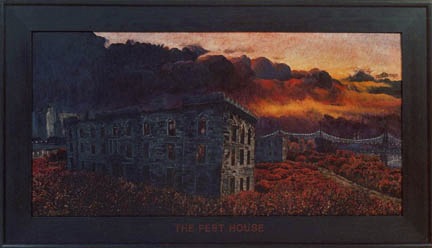

Statement for Art and the Law

So many people dream of owning an island to escape from society that we forget how many islands have been used to remove people from society. Blackwell’s Island in New York, for example, was used to incarcerate not only criminals, but vagrants, the disabled, the poor and those infected with disease. As social agendas have changed, most of these old facilities have disappeared; the ruins of the old smallpox hospital on Blackwell’s (the Pesthouse) remain as a monument to our darker days. But monuments may not be needed, as poverty and illness are again being looked upon as crimes. We put more effort in hiding the homeless than helping them. Those with AIDS must worry not only about their health, but whether the law will protect their rights or take them away in this new atmosphere of fear.

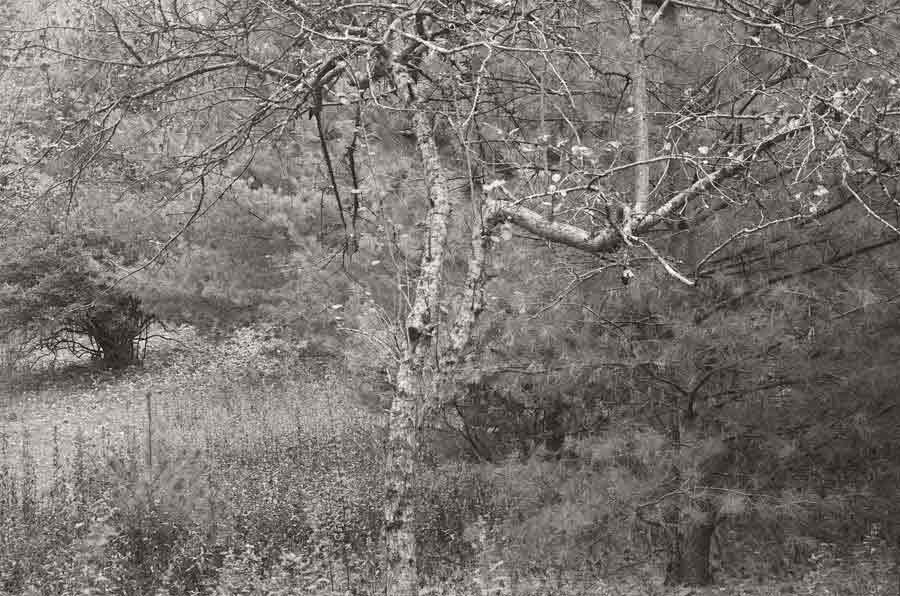

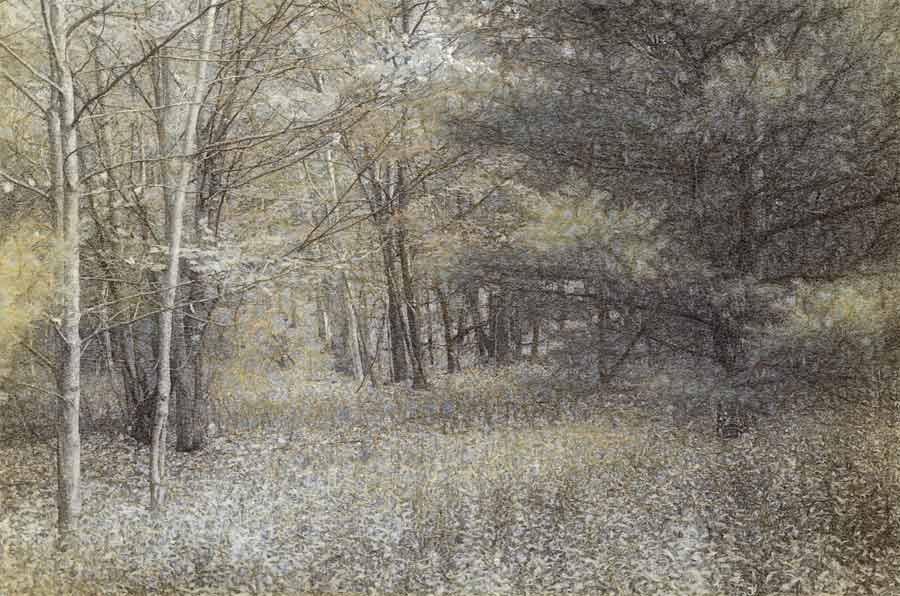

Statement for the exhibition, Landscape

To view one of Petrulis’ landscapes is to se something both strange yet familiar at the same time. The paintings are unlike those normally seen in landscape shows. There is something askew about them but it is just this uniqueness that draws one into the work. They have a presence which strikes something deep within. The work is not a realistic rendition or even an interpretation but an interaction between artist and place. Petrulis converses with the land as one would dance to music, adding his own mood and meanings. The work invites the audience to participate in the relationship between artist, place, and painting, and through this process to stimulate the viewer’s own connections to some hidden aspect of the land. It is a journey that is presented rather than a destination. A poetic mystery is captured larger than place or moment, the subconscious awakened by something magical within. This is the very same magic that is often used in tribal societies, where the distinction between art and life begins to disappear.

In our age many artists do not want to confront such issues. Others claim to convey this magical element by incorporating stylistic gimmicks, borrowed from sacred images, as if that alone creates meaning or makes up for what one lacks inside. Petrulis uses a personal vocabulary, drawn from experience, creating a magic space of his own. The creation of the work is like a fertility rite, not for crops or game but for the soul. These are not icons to be worshipped but an invitation to contemplation. The work is spiritual more in the tradition of the early Modernists than of the Romantics. It is not the land that is sacred but the connections one can make with it. For the uninitiated the subtleties may be slow to appear but there is much to be found within this work for those willing to look within themselves.

Statement for Journeys North and South: A Line of Moments on the Hudson

Long has the Hudson Valley been filled with artists and travelers, many with romantic visions of the sublime, others with more practical notions of creating a pictorial survey. Modern technology now allows us to make maps from satellites, keeping the mud from our boots while picking up such detail as the names on street signs. But seeing detail alone is not to know a place. One must travel through it, see its variant moods through changing weather and seasons. Alan Petrulis has done just that. Traveling up and down both banks of the Hudson by foot, he has captured a sense of place whose intimacy would be lost by any less personal means. For him these walks have become ritual, slowly creating a living map of the valley. The photographs in this series are a record of these walks. In seeking the valley he has discovered that it has no bounds or limits, that time renders it infinite, leaving no way to completely contain one’s experience of it. The photographs do not as much portray the place as they are a portrait of the artist. Each view, enhanced by text, represents a state of mind inspired by journey through the landscape. In this series many faces of the valley are to be found. The river appears in almost every scene, be it near or distant, as the driving force of a quest, from which one must never stray too far.

Statement for The Other Side of the Bridge: Landscapes of New York’s Outer Boroughs

Open a book on New York and you are likely to find many illustrations of Manhattan’s magnificent skyline, Central Park, Times Square and perhaps views of its many famous avenues. Brooklyn, if represented, will be done so by its famous century-old bridge with Manhattan spanning the horizon as a panoramic backdrop. Queens, Staten Island, and the Bronx will most likely not be included. Rarely do these boroughs appear as anything more than a footnote. Whether in a book or gallery show, it is unusual to find any departure from this formula. Most often landscapes of New York end at the rivers surrounding Manhattan Isle. In this series by Alan Petrulis, the landscapes also end at the same waterways, but from the other side of the bridge.

The constant focus on Manhattan as being “New York” has made most forget that it is only a part of a larger whole. The other four boroughs that comprise New York City have become a virtual wilderness to the uninitiated and especially to those who dwell in Manhattan. It is to this wilderness that Petrulis is drawn as earlier artists were drawn to uninhabited and exotic lands. Many have looked toward the wilderness in search of realities they could not find in an urbanized society. Petrulis seeks the same but from within. The prints and paintings of this series are a direct result of long walks totaling hundreds of miles taken throughout the city. When traveling by foot, New York becomes a vast land of dissimilar, everchanging views. A unique solitude has been captured in this city of millions within which a haunting melancholy pervades. For Petrulis the city is a special place for which he feels a close intimacy. This sense of place is a prime ingredient in his work.

New York is a city of great change. Every day a building is raised, a tree cut, a new foundation laid. Many of the sites we take for granted are slowly disappearing. The commonplace is rarely given any thought until one reaches back in memory only to discover what one sees no more. The subject of many of these landscapes is exactly that: the disappearing. What are pictured are not great historic sites or famous buildings, but that which too many of us pass by without notice. It is not out of nostalgia that these locations are documented, but for their importance in creating a greater, more complete consciousness of what New York is at this time. Although indebted to the language of tradition, these works are truly contemporary views in both subject and state of mind.

Yet to consider these works as documentary only is to miss the special value of them. They are about the reality of the unseen, capturing the spiritual forces hidden beneath the surface of the commonplace. The landscape is addressed as one addresses a person, becoming aware of the other’s moods, passions and attitudes. Petrulis’ reality is one of mystery and an intuitive understanding of the unknown. Within each piece there is much meaning to be deciphered. The answers to the questions raised by many of these works can only come from within; the meaning is as deep as the viewer’s contemplation.

Ultimately, Petrulis’ landscapes are where he keeps them in memory, not where they are. They are truly landscapes of the mind. And yet the emphasis of these works remains on content not self expression. They are not meant to be exclusively personal visions but those to be shared.

Documentation, change, solitude, contemplation: the works include all of these. But mostly it is presented as a sacrament to those initiated, those who sense the living spirit in the land, not only as a metaphor but as something truly real.

Alan Petrulis Copyright 2016 All Rights Reserved